1835 – The Last Men Hanged for Buggery

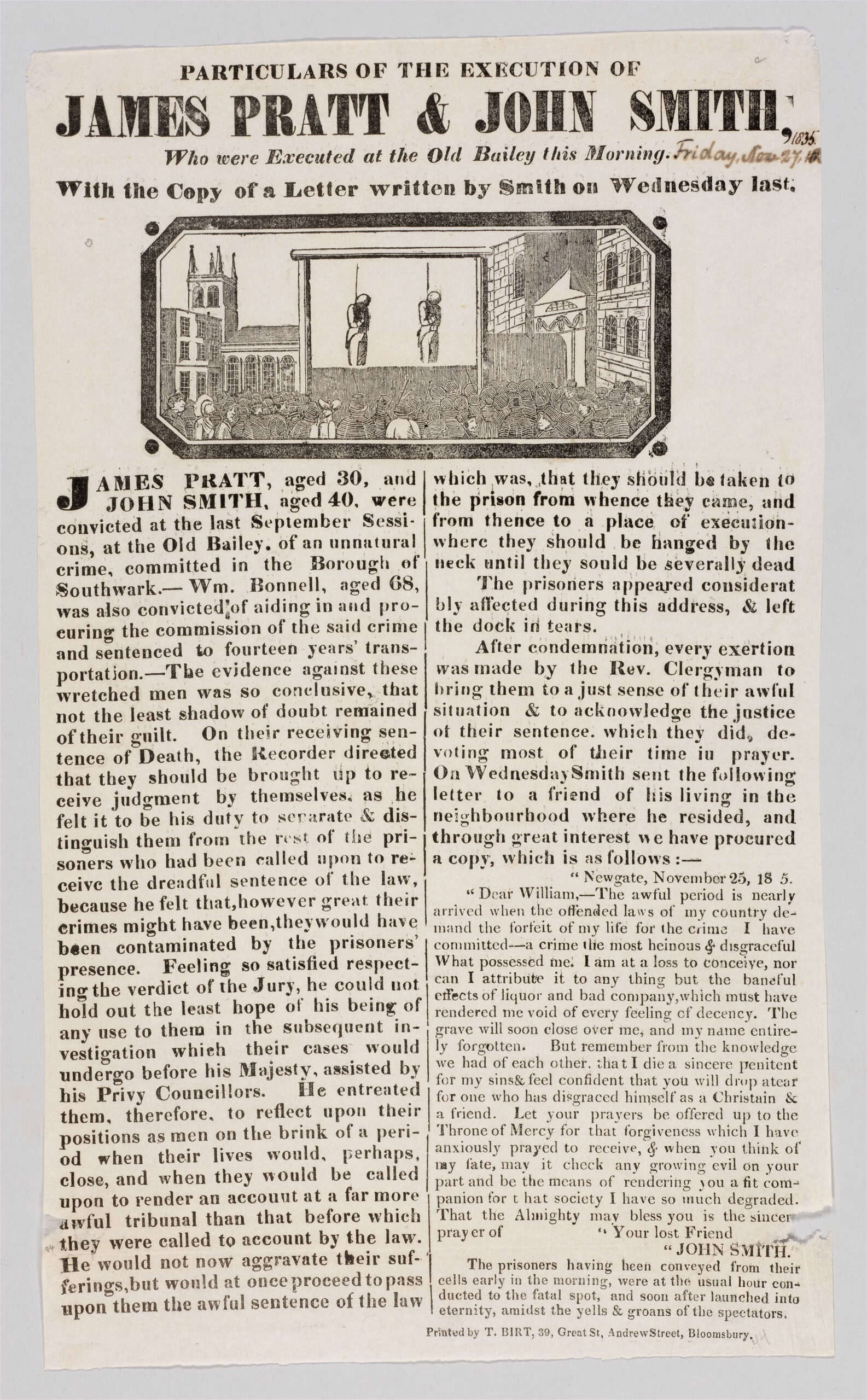

In the early nineteenth century, much of the news of England’s murders and executions was brought to the masses through penny and half-penny broadsides. These papers were published by a number of printers in the Seven Dials neighbourhood of London. The picture above shows a contemporary Broadside that is part of a scrapbook in The Harvard Law School Library – View It Here

Between 1806 and 1835, 404 men were sentenced to death for sodomy in England, of whom 56 were hanged and many more punished through transportation.

In this post we explore local connections to James Pratt and John Smith who were the last two men to be hanged in England for the crime of ‘buggery’ (anal sex).

There was a third man in the dock when the case was heard – William Bonell – who was the tenant of the rented room where the so called crime took place.

Pratt and Smith had been discovered in Bonnell’s room by the landlord Mr Berkshire and his wife who had taken it in turns to peer through the keyhole before calling the police.

The police magistrate that the men were bought before was Hensleigh Wedgwood, the fourth son of Josiah Wedgwood II – a family that is very well known in the history of the Potteries.

When the three men were tried at the old bailey James and John were sentenced to death. Hensleigh Wedgwood was appalled by this and attempted to save them from execution.

Politician and historian Chris Bryant sets out a full and detailed account in his recently published book – James and John.

The Peter Tatchell Foundation also has an excellent article about this case view the article here

Scroll down this page to read more about our local connection to this history and Hensleigh Wedgwood’s passionate appeal to the home secretary

William Bonhill was baptised in Bilston, Wolverhampton on 23 September 1769, his parents were Robert Bonell and Ann. Robert was from Farewell, a small village on the eastern side of Cannock Chase and his wife, Ann Ironmonger came from nearby Penkridge.

James Pratt was baptised on Easter Sunday, 10 April 1803. His parents were John and Anna Pratt and their family home was in Essex.

We know less about John Smith but the chaplain, of Newgate prison recorded that he was from Worcester, though this more likely meant ‘Worcestershire’.

James and John came from working-class backgrounds and in common with many such people of the time they had moved to London in search of employment.

William Bonill, aged 68, had lived for 13 months in a rented room at a house near the Blackfriars Road, Southwark, London. His landlord, Mr Berkshire, noticed he had frequent male visitors, who generally came in pairs. On the afternoon of 29 August 1835, when Pratt and Smith came to visit Bonill, landlord Berkshire spied on them through the keyhole to the room. He saw James and John engaged in sex and called his wife to take a look – then they called the police. Bonill was absent from the room but returned shortly after with a jug of ale.

When James Pratt, John Smith and William Bonhill appeared before Magistrate Henleigh Wedgwood, the evidence compelled him to commit the men to trial at the Old Bailey. All three were found guilty. Pratt and Smith were sentenced to death by hanging and Bonell received a sentence of transportation to Van Diemen’s land where he died in 1841. (Van Diemen’s Land was the colonial name of the Australian island of Tasmania)

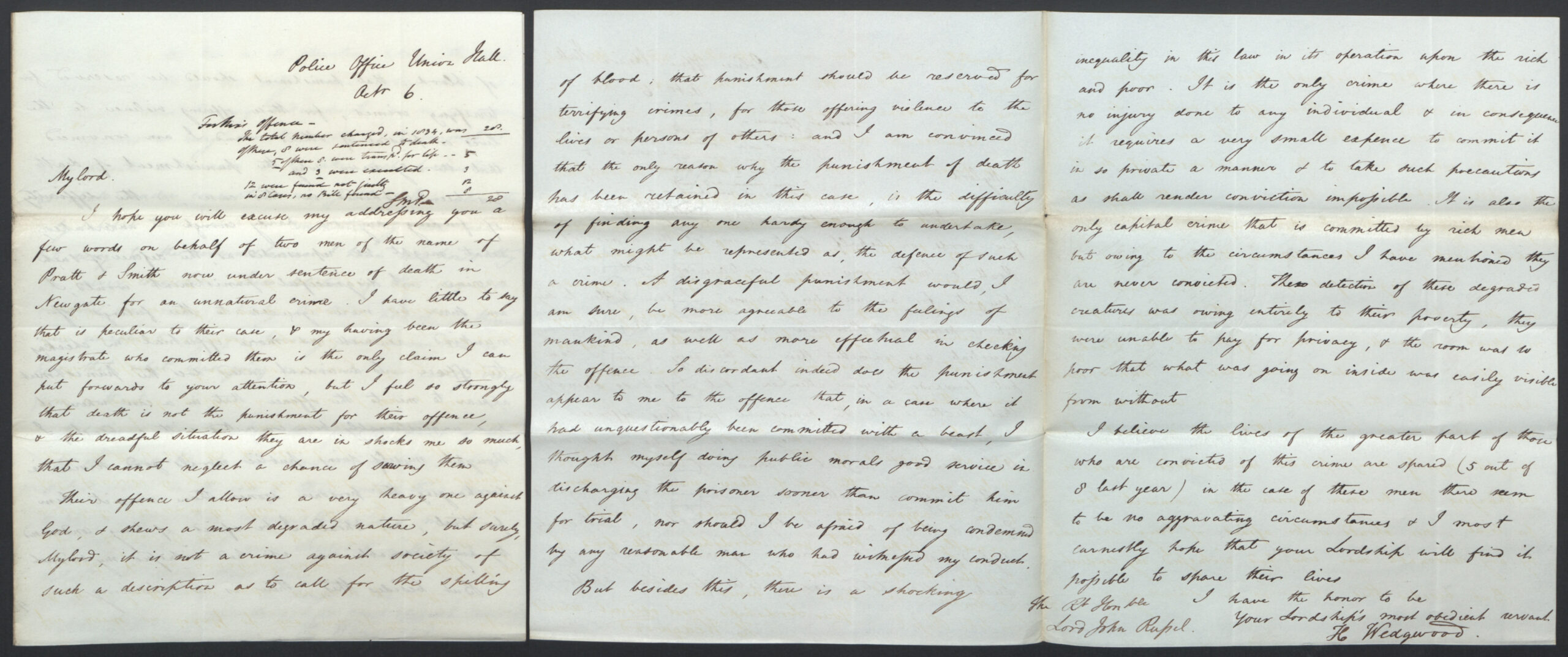

Hensleigh Wedgwood was appalled at the harsh sentences given to Pratt and Smith and wrote a passionate letter appealing for clemency. Bonell’s landlord Mr Berkshire and his wife who had given evidence as witnesses, also wrote letters of appeal thinking the sentence to be far too harsh. Despite these letters and others submitted by family members the two men were hanged.

Here is the letter submitted by Hensleigh Wedgwood along with a transcription below.

This letter is part of a collection of papers in the National Archives

Transcript of the letter from police magistrate Hensleigh Wedgwood to the Home Secretary Lord John Russell

My Lord,

I hope you will excuse my addressing you a few words on behalf of two men of the name of Pratt and Smith now under sentence of death in Newgate for an unnatural crime. I have little to say that is peculiar to their case and my having been the magistrate who committed them is the only claim I can put forward to your attention, but I feel so strongly that death is not the punishment for their offence and the dreadful situation that they are in shocks me so much that I cannot neglect a chance of saving them.

Their offence I allow is a very heavy one against God, and shows a most degraded nature, but surely, Mylord, is it not a crime against society of such a description as to call for the spilling of blood, that punishment should be reserved for terrifying crimes, for those offering violence to the lives or persons of others: and I am convinced that the only reason why the punishment of death has been retained in this case, is the difficulty of finding any one hardy enough to undertake what might be represented as the defence of such a crime. A disgraceful punishment would, I am sure, be more agreeable to the feelings of mankind, as well as more effectual in checking the offence. So discordant indeed does the punishment appear to me to the offence that, in a case where it has been committed with a heart, I thought myself doing public moral good service in discharging the prisoners sooner than commit them to trial, nor should I be afraid of being condemned by any reasonable man who had witnessed my conduct.

But besides this, there is a shocking inequality in this law in its operation upon the rich and poor. It is the only crime where there is no injury done to any individual and in consequence it requires a very small expense to commit it in so private a manner and to take such precautions as shall render conviction impossible. It is also the only capital crime that is committed by rich men but owing to the circumstances I have mentioned they are never convicted. The detection of these degraded creatures was owing entirely to their poverty, they were unable to pay for privacy, and the room was so poor that what was going on inside was easily visible from without.

I believe the lives of the greater part of those who are convicted of this crime are spared (5 out of 8 last year) in the case of these men there seems to be no aggravating circumstances and I most earnestly hope that your Lordhsip will find it possible to spare their lives.

I have the honour to be your Lordship’s most obedient servant

H Wedgwood

Hensleigh Wedgwood born 21 January 1803 was was the fourth son of Josiah Wedgwood II whose father was the great master potter Josiah Wedgwood of Stoke-on-Trent.

The letter written in defence of James Pratt and John Smith was a brave act suggesting a man with a social conscience ahead of his time. Capital punishment for buggery remained in British law until the enactment of the the Offences against the Person Act 1861. However, nobody else was hanged after the case of James and John in 1935.

Hensleigh Wedgwood died on 2 June 1891 at his house in London. According to internet sources he was buried at the Church of St. Peter ad Vincula in Stoke on Trent. This fact that has not yet been verified.

More LGBT+ History Pages